We all feel more “alive” on some days compared to others. Some people call it “being in the zone”, or “flow”, where you seem more responsive to the world, able to make better, faster decisions. Wouldn’t it be nice to feel that way more often, maybe even all the time?

Well, as with any attempt to improve something, the first step is to measure the effect, and then try to notice what foods or activities make it better. Unfortunately, it can be hard to tell objectively whether you have more energy than yesterday because after all, you rely on the same brain to tell you whether you feel smart or not. On days when you’re not so energetic, maybe your brain is fooling you.

The late Seth Roberts developed some simple measurement techniques that attempt to tell objectively how smart you are right now so you can compare yourself to the way you felt yesterday, or a few weeks from now, perhaps based on some new type of food you are eating. Seth and I were working on an iPhone version of this test when, tragically, he passed away, but I’ve continued to develop the software ever since and recently came upon some results that I thought were interesting.

How I measure myself

“Brain Reaction Time” (BRT) is a four-minute test that I give myself within an hour after waking up every morning. I don’t think it matters much when or where you do it, though to be as consistent as possible, I try to tie into my daily coffee-drinking ritual — a regular time and state of mind for me, before the rest of my family gets up. The BRT resembles what psychologists call a “vigilence test”, which airline pilots and others in stressful situations can take to see if they’re fit for service. But the BRT I was working on with Seth can measure things that are much more subtle, and I’ve been using it to tell how or what aspects of my life are improving my ability to focus.

Along with my BRT scores, I track another ton of variables (exercise, sleep, vitamins, food) which I enter daily in an Excel spreadsheet. I’m working to make this much more automatic using the excellent Zenobase site, but for now the important thing is just to track it however I can.

Results: Fish oil makes me smarter

I occasionally take one or two Kirkland signature brand fish pills in the morning, and of all the different things I track, I was surprised that something so simple could have such an obvious effect on my brain reaction time.

Here is the summary chart based on the past three months of testing:

The red and blue lines are the linear model, or trend lines for each variable. You can think of them like an average, the exact mid-point of all the points through time.

If you know something about statistics, we can run a simple T-test:

##

## Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: rik$ptile[rik$Fish.Oil == 0] and rik$ptile[rik$Fish.Oil > 0]

## t = -2.2129, df = 54.212, p-value = 0.03113

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -15.3903411 -0.7599052

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 44.10345 52.17857

In other words, we can say with 95% confidence that the effect is real. The p-value, which is almost zero, is powerful evidence that whatever is going on is not due to chance.

What else might matter?

I tried my test on several other variables. For example, here’s how my scores look on days when I’ve had a glass of red wine or beer:

Again, statistically you can see the difference when we do the T-Test:

##

## Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: rik$ptile[rik$Alcohol == 0] and rik$ptile[rik$Alcohol > 0]

## t = 0.3831, df = 69.495, p-value = 0.7028

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -5.827448 8.598423

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 50.22222 48.83673

The p-value is much higher – so high in fact that we can assume that alcohol really has no effect.

How about Vitamin D? Here’s the result:

##

## Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: rik$ptile[rik$Vitamin.D == 0] and rik$ptile[rik$Vitamin.D > 0]

## t = -1.134, df = 41.954, p-value = 0.2632

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -11.408090 3.199757

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 46.33333 50.43750

Perhaps a tiny effect, but that high p-value says it’s pretty unlikely. Since I usually (but not always) take Vitamin D on the same mornings I take fish oil, I’m pretty sure this is just an artifact of the data.

Fading Effects

How long does the fish oil effect last? I test about 24 hours after taking two pills, but will the effect remain a day or two later?

If the fish pills help, then I’d expect the improvement to fade a bit each day after I stop taking them. And that’s exactly what I get:

See how my “Fish Oil” scores decline as I get further from the day I took the pills? If the effect were truly random, you wouldn’t expect such a constant slope in the graph. It really does seem like something is going on here.

Sleep doesn’t matter

Okay, perhaps I’ve convinced you that fish oil helps improve the scores on this test. But we all know that good sleep is perhaps the single most important factor in how well we feel. Maybe the fish oil just helps ensure a good night’s rest?

Nope. I track my sleep very carefully, using a Zeo headband that can tell precisely when I fell asleep, and whether or how long I might have been awake in the middle of the night.

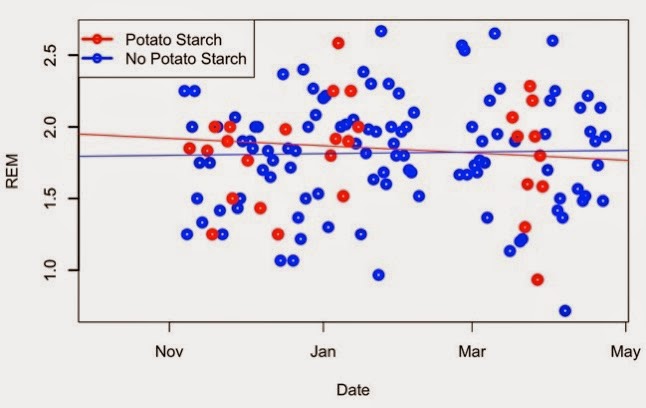

Surprisingly, sleep seems to make no significant difference in my test scores. Here’s a graph, with blue dots showing my scores on days when I slept less than my average, and red dots when I slept more. See any patterns? (I can’t either)

##

## Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: rikN$ptile[rikN$Z <= meanZ] and rikN$ptile[rikN$Z > meanZ]

## t = 0.6063, df = 80.505, p-value = 0.546

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -4.799337 9.005546

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 50.51220 48.40909

Again, the high p-value, plus the similarity between the two means is pretty good evidence that sleep has little to do with my BRT.

Conclusions

This is not the first claim that’s been made about the relationship between food and BRT. Seth Roberts noted that he scored higher after eating butter, and Alex Chernavsky showed that BRT is affected by caffeine.

I’d need a double-blind study, perhaps conducted with dozens or hundreds of individuals to “prove” these results scientifically, but that’s not the point of this test. I found something that apparently works consistently for me, and it lets me easily test many other types of variables. By looking at other outliers in my BRT results, I hope to find other foods and activities that can make me smarter too.