Zeo was, for many of us, our

favorite QS company: great, consumer-oriented low-cost hardware that measured something useful (sleep) to give insights we couldn't have had otherwise. After $20M+ in funding over the better part of a decade in existence, they went bankrupt, abruptly -- so quickly in fact that many customers couldn't even get their data off the machines.

In one of my favorite sessions at last week’s

Quantified Self Conference in San Francisco, Zeo co-founder Ben Rubin joined a few other co-founders to discuss why their original dreams didn’t quite pan out.

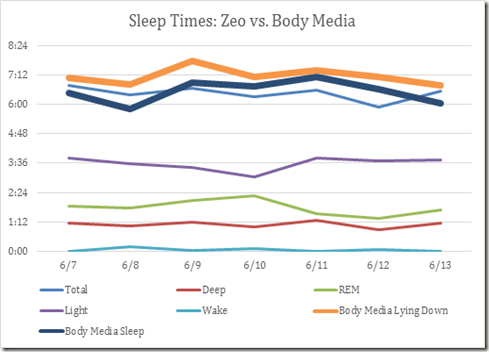

Zeo’s biggest success factor, says Ben, was "persistence" -- to build a great product, get retail distribution in places like Best Buy, expand internationally to the UK, build a portable Bluetooth version -- but the same persistence was also the seeds of their undoing, when they continued to push sales- and marketing-wise even when it was clear that the mass market didn't want the headband they were selling. Sleep measurement alternatives popped up from the fitness band companies, and although

they weren't nearly as precise, it became harder to explain the Zeo advantage. Zeo needed a similar passive solution (maybe something you attach to your bed, like

Beddit), and they were working on it, but persistence takes a toll on founders -- one left in 2010, Ben left in 2011 -- and the

professional management team that remained found themselves confronting the worst of all worlds: a market that said not "yes" or "no", but a dreadfully-ambiguous "maybe".

Ben’s advice to anybody thinking of a similar venture is to fit, somehow, into the lives that people live

right now. You may be trying to change behavior (isn’t that the point of measuring it?) but the mass market wants a straight line from where they are

right now. You can’t ask them to uproot existing habits to use your product.

So what happened to Zeo's assets? Will the products ever be revived? Ben obviously has to be discreet when discussing confidential information, so all he would say is that it was an asset sale by “a medical company interested in sleep." So who knows. He also, sadly, confirmed my worst fears, that he knows of no way -- even through reverse-engineering -- to get your Zeo data. The company failed so quickly that the people in charge of maintaining the servers had no time to close things gracefully. It's gone.

Brian Krejcarek, founder of Green Goose, had another exciting product that failed: $4 attachable "stickers" with embeddable sensors you can place throughout your house -- on your toothbrush, your bike, your dog. It was a brilliant idea, and they quickly attracted $1.3M of funding. But the direct-to-consumer company is super-tough – how do you get the word out? how do you handle the logistics? Meanwhile, technology marches brutally forward, and the wireless base station that originally made the stuff work at great (but elegant) engineering cost, is now available on Bluetooth 4.0 and your iPhone for next to nothing.

Chris Hogg, co-founder of personalized health prediction startup 100Plus, had a comparatively happy ending: his company was sold, to

Practice Fusion (a $70M Series D funded medical records company). But Chris left when that happened, because he was always more interested in the “personal” side of health, not Big Enterprises, which is where the company ended up making its first money. In fact, that was one of his pieces of advice: “be careful where you get that first dollar, because that’s all next your investors will want to talk about.”

That’s the tension in every new business: on the one hand, you want to be flexible and listen to your customers; but on the other hand, you want to be true to your original mission. When you find that consumers don’t bite, either because the product’s wrong or the technology has moved on or that enterprises turn out to be more interested, you may find that your original dream no longer applies.

All three entrepreneurs knew their original ideas were worthwhile and we’ll get there someday. But sometimes the future happens later than we’d like.